Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

The U.S. trade war feels like a sequel to a successful blockbuster action movie. Similar to the way producers try to outdo their own explosions and car chase scenes in a second film, President Trump’s second trade war is bigger and bolder than the first installment in 2018. By broadening the number of targeted countries and the sheer scale of tariff rates, he is making his own series of trade actions from seven years ago look almost tame.

The market response has, accordingly, been larger. The S&P 500 fell 12% from April 2 to midday on April 9, bringing the cumulative loss from the February 19 peak to just over 20%, with a broad selloff in U.S. Treasuries sending long-term yields higher. The 90-day pause on “reciprocal” tariffs on April 9 stemmed the market ructions and amounted to a détente during which trade deals could be struck. Encouraged by the developments, investors pushed the S&P back up to just about 12% below its peak in mid-April.

But the current state is unlike a movie where all the issues are resolved. Trump’s pause did not revert tariffs to pre-trade war rates, but instead to levels not seen since the early 1900s. Investors have been left pondering whether the U.S.’s new global minimum tariff of 10% is a ceiling—that successful trade deals could bring down—or if it’s a floor. To us, this is the critical consideration in determining whether the U.S. and global economies are headed toward recession or continued growth. We think a reasonable case can be made that we are at a ceiling, but with President Trump keeping his cards so close to his vest, we place very little conviction on that assessment and remain cautious in portfolios.

President Trump’s decision to give a 90-day pause on the jaw-droppingly high tariffs all but removes the “armageddon” or worst-case scenario from the table, in our view. A global minimum of 10% on all trading partners (excluding China, for the moment, which we discuss below) would still likely lead to a recession, in our view, but it’s a close call, and it’s critical in determining whether this new rate is a ceiling or a floor.

The challenge in judging the future of tariffs is that President Trump and administration officials have given two different goals for this effort. For roughly a month as he teased the April 2 announcement, President Trump presented reciprocal tariffs as an effort to level the playing field. “They charge us, we charge them,” he said multiple times in explaining that he would match all countries tariff-for-tariff so that U.S. firms were facing fair competition. That says nothing of the outcome; it just ensures the rules are fair and let the chips fall as they may.

The surprise from the April 2 Rose Garden announcement was not just the astronomical tariffs being levied, but also that the administration had jettisoned the level-playing-field approach in favor of a results-based approach geared toward eliminating U.S. trade deficits with each country. That is in sync with the view that Trump has consistently expressed over years and decades that trade deficits are undesirable and should be eliminated.

Negotiating equal tariffs and fairness could be straightforward and potentially lead to very low tariff rates, suggesting that today’s are a ceiling. It would require some agreement on tariff rates and some admittedly thornier but manageable issues on currency management and non-tariff barriers. There is potential that trade deals could be made over the course of the 90-day pause, as well as extensions of the pause if progress is being made. We think this would be supportive of equities and risk assets.

However, if the administration insists on a trade policy that is designed to eliminate all deficits, then today’s rates are more likely to be a floor. If this is the case, we believe investors would need to prepare for disappointing news over the 90 days and more market volatility.

The other key consideration is the evolution of trade relations with the world’s second-largest economy. At each step of the way since taking office, President Trump has been harsher on China—now reflected by the cumulative 145% tariff on goods. Even as Trump paused the reciprocal tariffs on other nations he increased tariffs on imports from China as the two countries retaliated back and forth. Our estimates of the total tariff burden showed the additional levies on China actually canceled out most of the reprieve from dropping all other countries down to 10%. Trump later exempted all smartphones, tablets, semiconductors, and many related items that amount to nearly a quarter of imports from China. That was accompanied by messages that such goods would soon be subject to individualized tariffs.

That said, there are hopeful signs. Trump signaled the brinksmanship with China had peaked, saying he “couldn’t imagine” raising tariffs any higher on the world’s second-largest economy, and spoke about President Xi in flattering terms. But on the same day Treasury Secretary Bessent indicated, perhaps, another goal of the administration, saying “I think at the end of the day we can probably reach a deal with our allies…and then we can approach China as a group.”

Ultimately, we expect some kind of deal with China that will reduce the exorbitant rate. President Xi is not likely to back down for fear of losing face—and control—and has tools at his disposal he can leverage during the talks. These include a massive hoard of U.S. Treasuries as well as control of most global production of rare earth elements that are critical to high-tech products.

In addition to echoing the first Trump presidency, the second trade war also risks repeating its own form of the acute supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic. We have learned the hard way that supply chain chaos can lead to unexpected and unwanted inflation. Here, we are particularly focused on the supply chain implications of these tariffs for business activity, consumer confidence, and inflation alike. Businesses small and large will see significant revenue declines if they cannot obtain needed componentry or can only do so at costs that are untenable. For some, the challenges will be existential. Consumers may confront bare shelves for certain items, ranging from apparel to electronics. Last but not least, as consumers have no choice but to pivot to domestic alternatives, price increases in many areas of the economy could experience a temporary albeit acute upward spiral. All of these effects would contribute to a downturn.

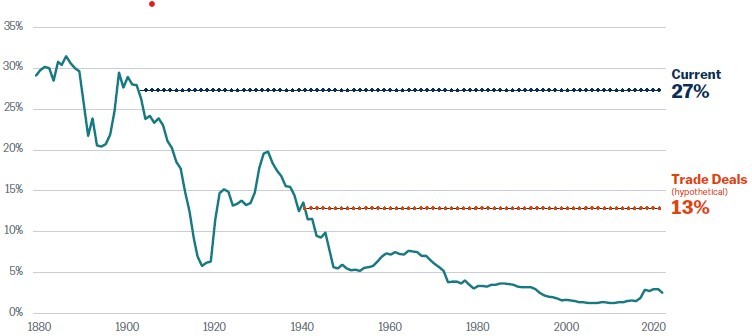

We calculate today’s tariff rates amount to an overall effective rate of 27%, using 2024 import levels (Figure 1). That is a ten-fold increase from where we started the year and the highest in 120 years. We believe this would lead to a recession, but also that it will be brought down soon. Additionally, we think trade flows from China will be redirected through other countries and face the 10% rate.

Consider a hypothetical where the administration reaches agreements with China where the tariff is reduced to 25% while all other countries successfully avoid their reciprocal rate, and all face the 10% global minimum. This includes a 10% rate for Mexico and Canada who are currently facing rates of 25% and 20%, respectively, but with exemptions for some USMCA goods. We calculate that the resulting effective tariff rate would be 13%, which combines the starting point from January 1, the incremental global minimum of 10%, and the additional tariffs on steel and aluminum enacted in March, as well as a tax hike of $430 billion. When combined with the impacts of uncertainty and wealth effects from equity market weakness, this would likely lead to recession but is a close call.

Figure 1: How low could tariffs go?

U.S. Effective Tariff Rate

Sources: Yale Budget Lab, Wilmington Trust.

Figure 2: Asset class positioniing

High-net-worth portfolios with private markets*

* Private markets are only available to investors that meet Securities and Exchange Commission standards and are qualified and accredited. We recommend a strategic allocation to private markets but do not tactically adjust this asset class.

Data as of 3/31/2025.

Positioning reflects our monthly tactical asset allocation (TAA) versus the long-term strategic asset allocation (SAA) benchmark. For an overview of our asset allocation strategies, please see the disclosures.

If that hypothetical 13% is a ceiling and the administration negotiates rates down to a fair and lower playing field, then the chance of recession is reduced with each increment down. If the administration insists on the global minimum, then the hypothetical line is a floor, and will only rise with failed trade deals and additional (threatened) levies on products such as pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. Recession risk, and severity, rises with each increment higher.

We think there’s a reasonable argument that negotiations will bring rates down incrementally, but not with strong enough conviction that it merits putting more risk into portfolios. The experience thus far in 2025 argues for caution, so we currently hold portfolios at neutral to long-term benchmarks across all asset classes (Figure 2). If a day comes when we get conviction of which way it will break, we would adjust portfolios accordingly. But this movie producer is far too unpredictable, so we will watch how it plays out for now.

Please see important disclosures at the end of the article.

Please complete the form below and one of our advisors will reach out to you.

* Indicates a required field.

Stay Informed

Subscribe

Ideas, analysis, and perspectives to help you make your next move with confidence.

What can we help you with today