Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

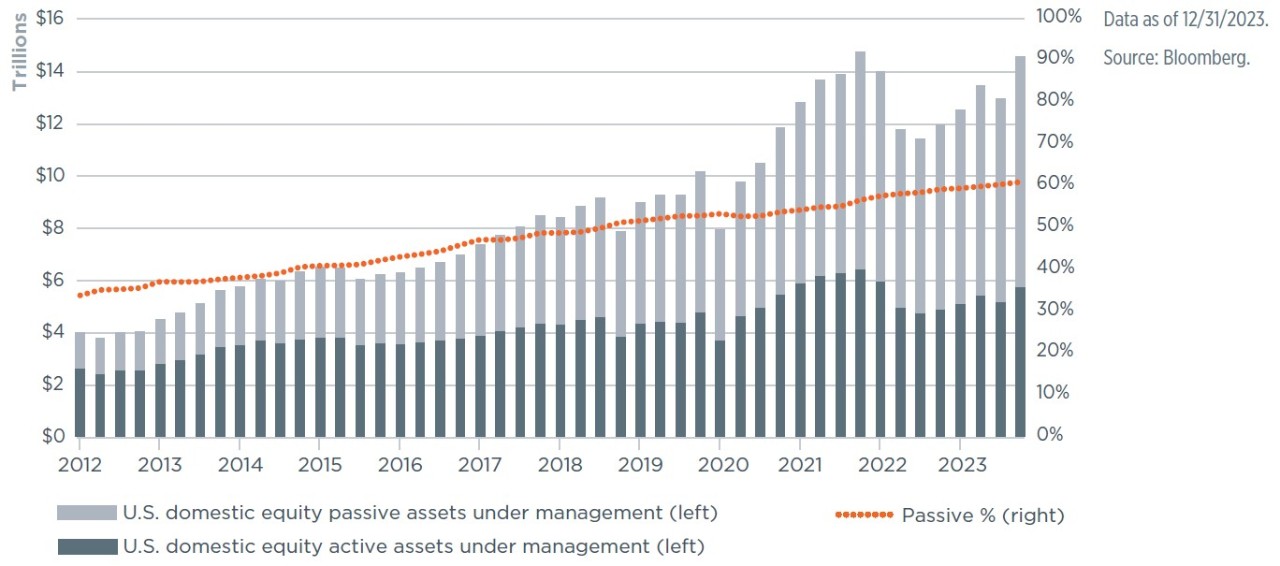

The growth of passive investing over the past decade has been a key development in the global asset management industry. Passive management—which includes index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) as well as direct indexing—has steadily gained in popularity and evolved rapidly since the first public indexing strategy was launched in the 1970s. Passive strategies seek to replicate the performance of a market index while keeping fees to a minimum. Active strategies, in contrast, strive to outperform the market, net of fees, by relying on managers' research and analytical skills to buy and sell individual securities. In general, they also charge higher fees due to the additional costs of management and the potential to earn excess returns relative to the market. These excess returns are often referred to as “alpha,” whereas the passive benchmark exposure is referred to as “beta.” In this sense, passive management provides an inexpensive way to obtain beta, while active management offers the potential to generate alpha. Today, passively managed assets comprise more than half of all U.S. domestic equity strategies (Figure 1).

The prominent role of passive strategies in the investment management industry today raises the question of how to best utilize active and passive in portfolios. At Wilmington Trust, we do not think the right question is “active or passive?” Rather, we think both active and passive management have a place in the portfolio construction process, while recognizing that each client will approach investing with a unique set of risk and return goals. Having a diversified platform of strong investment vehicles is important to the successful integration of active and passive strategies into portfolios. An in-depth understanding of which asset classes and market environments provide the greatest opportunity for each type of strategy is critical for portfolio construction. The focus of this piece is communicating Wilmington Trust’s research behind and approach to combining active and passive strategies in portfolios.

Figure 1: The shift from active to passive persists

Passive management as a percetage of U.S. domestic equity strategies

While passive investing was introduced in the 1970s and has enjoyed growth since, inflows into passive vehicles accelerated following the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, led by ETFs. Extremely low and even negative interest rates helped power the second-longest bull market in history from March 2009 to March 2020, as investors sought higher returns in risk assets. In this environment, almost every major asset class generated positive returns with relatively low volatility.1 Correlations (a measure of how closely securities move in relation to each other) within and across asset classes rose to historically high levels. With most asset classes delivering attractive real returns (after accounting for inflation and taxes) and not much differentiation across securities, the opportunity for security selection (also referred to as stock picking) was relatively limited, making it more difficult for active management to generate alpha.2 Against this backdrop, low-cost passive funds have attracted more investors, particularly in the U.S.

Passive management’s growing market share has introduced an environment of healthy competition, with traditional active strategies losing assets to their passive counterparts. This more competitive environment has contributed to declining fees across both active and passive funds. It may not be surprising that the average passive fund’s expense ratio (how much of a fund's assets are used for administrative and other operating expenses) dropped from 0.27% to 0.05% during 1996 to 2002.3 After all, one of the key benefits of passive investing is low-cost exposure to a benchmark. What is perhaps less obvious is that the average expense ratio of actively managed equity mutual funds has decreased from 1.08% to 0.66%—a decrease of 61%—over the same period. The widespread availability and adoption of passive and smart beta strategies—which seek to capitalize on specific style factors, such as value, quality, momentum, size, dividend, and low volatility—have led investors to demand more from their active managers.

In 1976, Vanguard founder John Bogle launched the first index mutual fund, aptly named the First Index Investment Trust, which enabled retail investors to closely track the S&P 500 index at a lower cost.4 The next important milestone was the introduction of the ETF, which offers a number of advantages relative to mutual funds. To start, while mutual funds only accept investor money or redemptions at the end of each trading day, investors have the ability to buy and sell ETFs throughout the trading day. ETFs also tend to have lower fees and, for taxable investors, generate less in tax liabilities. Mutual funds must buy or sell underlying securities in the strategy to meet investor purchases and withdrawals, which may trigger a taxable event. ETF inflows and outflows, by contrast, can be fulfilled through an in-kind exchange of baskets of securities, limiting the overall tax impact. Although investor enthusiasm for ETFs was fairly muted when they were initially introduced, assets under management (AUM) in ETFs have grown rapidly over the past decade, particularly in U.S. markets. Today, both index mutual funds and ETFs have expanded to cover every major index, and AUM continues to grow.

As technology has grown more sophisticated, so too has passive investing. Alongside the growth of traditional ETFs, we have also seen the advent of smart beta ETFs, which seek to capitalize on specific style factors that have been shown both in academic research and in practice to offer the potential for long-term excess returns. Rather than investing in a broad U.S. stock market index, it is now possible to invest in firms that provide exposure to certain “slices” of the market, such as firms exhibiting upward price momentum, higher value exposure (those that are less expensive across a variety of metrics), and higher quality (firms with characteristics such as lower leverage, higher profitability, and more stable earnings). At Wilmington Trust, we seek to use smart beta ETFs in an effort to obtain inexpensive exposure to desired style factors.

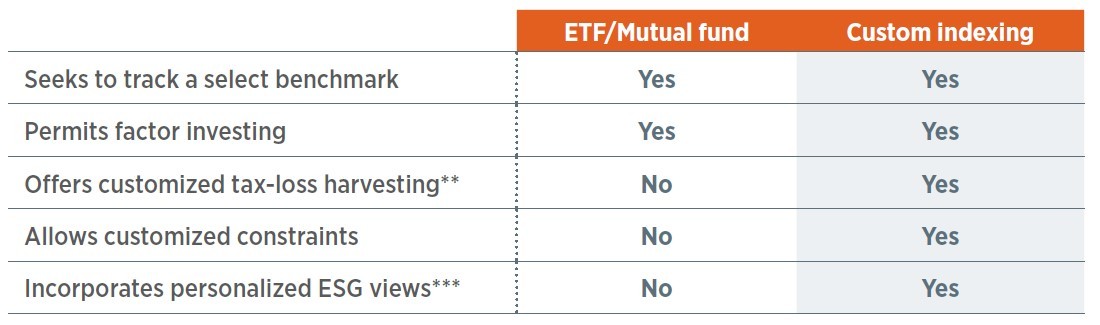

Figure 2: Custom index offerings (representative characterization)

Key benefits versus ETFs and mutual funds*

* Custom Indexing may have higher management fees than a comparable passive vehicle. Tax benefits apply to taxable investors. The level of customization may involve higher portfolio turnover which can incur higher transaction costs. Direct indexing is less accessible than an ETF or mutual fund, often with a minimum investment of $250,000.

** Tax-loss harvesting is the timely selling of securities at a loss to offset the amount of capital gains tax owed from selling profitable assets. Tax-loss harvesting involves certain risks, including, among others, the risk that the new investment could have higher costs than the original investment and could introduce portfolio tracking error into accounts. There may also be unintended tax implications. Prospective investors should consult with their tax or legal advisor before engaging in any tax-loss harvesting strategy. Taxpayers paying lower tax rates than those assumed, or without taxable income, would either earn smaller tax benefits or have no tax benefits from tax-advantaged indexing. Also, there is the risk that securities bought to replace securities harvested for tax losses may perform worse than the securities sold.

*** There is no guarantee that integrating ESG analysis will provide improved risk-adjusted returns over any specific time period. The evaluation of ESG factors will affect the strategy’s exposure to certain issuers, industries, sectors, regions, and countries and may impact the relative financial performance of the strategy depending on whether such investments are in or out of favor.

Source: Wilmington Trust 2023 (representative characterization of custom indexing offerings).

Finally, as technology has transformed every aspect of our lives, it has driven a new age in passive investing. In recent years, we have seen the growing popularity of custom indexing strategies. These strategies offer the cost and tax benefits of index funds and ETFs, while also providing additional advantages* for investors (Figure 2). Custom indexing uses sophisticated technology and analytics designed to create a portfolio that closely tracks the performance of a benchmark index, such as the S&P 500 or Russell 3000. This is similar to traditional passive investing; however, in the case of custom indexing, the investor owns the individual securities in a separately managed account (SMA). Ownership of individual securities in this structure provides investors with more control over their portfolios and allows for certain tax strategies—including the incorporation of low tax-basis stock and tax-loss harvesting—which may help reduce tax liability for taxable investors across portfolios. It also allows for a high level of customization, providing the ability to build a portfolio tailored specifically to an investor's personal values, investment goals, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) preferences. Since wealth management often incorporates a tailored approach, a custom indexing strategy may be a compelling solution to meeting evolving client needs.

We take a data-driven approach to assessing the opportunities for active and passive management. Our research indicates that certain asset classes and market environments provide more opportunity for active management. Manager due diligence and consideration of fees are critical elements of the portfolio construction process. Finally, a framework to allocate risk across beta, factor exposure, and active stock picking is key.

The opportunity for active management varies across asset classes. In general, less “efficient” asset classes offer more opportunity for active managers to generate returns in excess of the market. The most established definition of market efficiency is the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) as laid out by Eugene Fama, who won a Nobel Prize for his work. In its purest form, the EMH asserts that security prices reflect all available information. The real world, of course, is not the same as theory. The core concept, though, is that markets are mechanisms for incorporating and pricing information. Along these lines, we can define efficiency as how quickly and accurately a market incorporates information into prices. There are several characteristics consistent with more efficient asset classes:

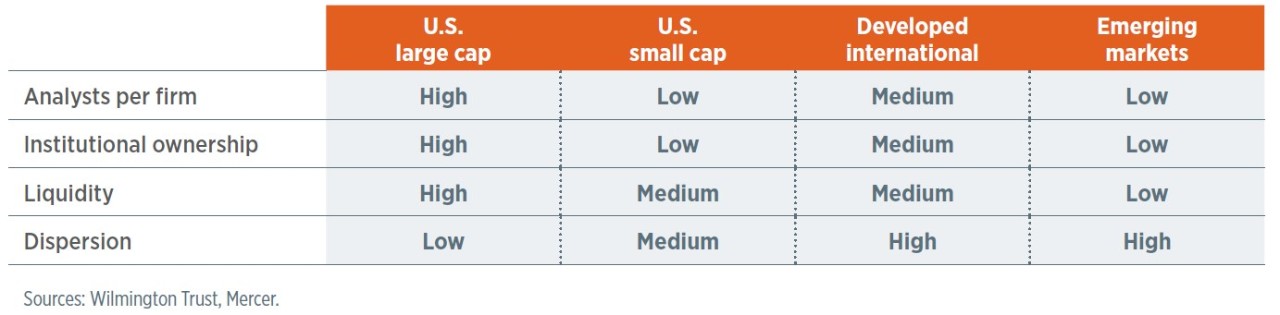

Figure 3: Characteristics of major equity markets

Market efficiency metrics

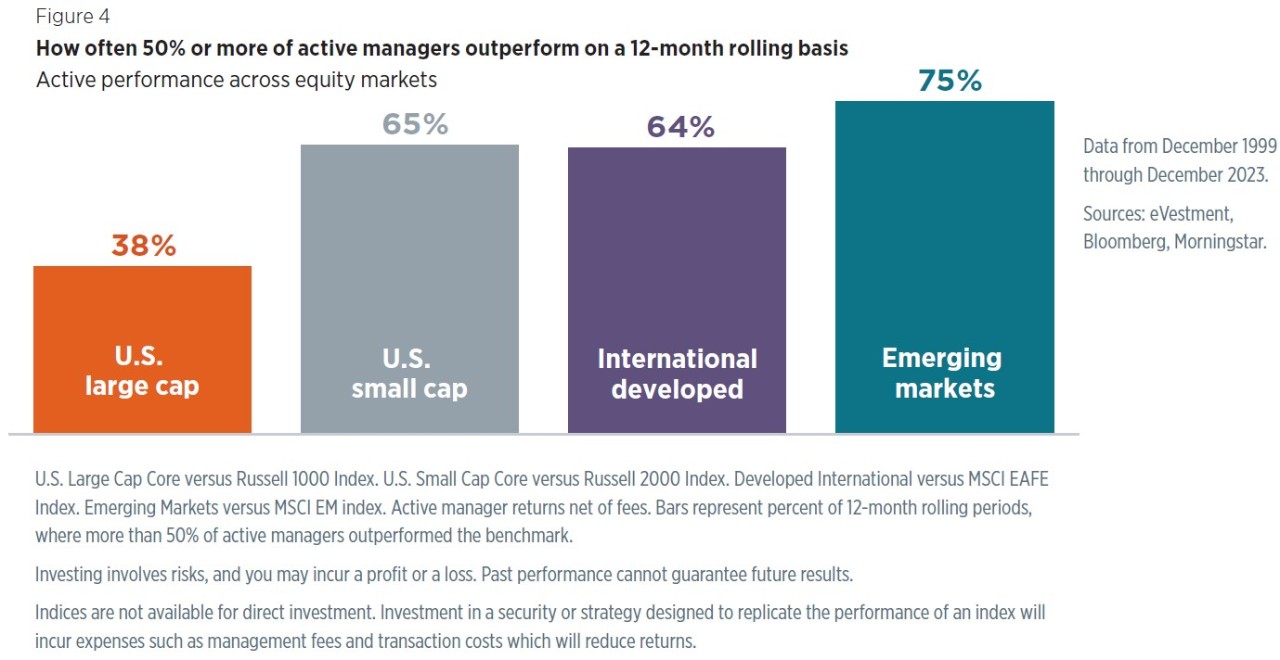

Figure 4: How often 50% or more of active managers outperform on a 12-month rolling basis

Active performance across equity markets

As one might expect, U.S. large cap consistently achieves a large quantity of trades and is the most efficient market in the equity universe. Recall that the key to efficiency is the ability to incorporate information into prices. The more research coverage a group of companies receives, the more likely a greater percentage of relevant information will be reflected in its prices. Small cap, for example, is relatively under-researched and more difficult to analyze while its larger brethren typically have greater analyst coverage, higher institutional ownership, and more readily obtainable data. Figure 3 highlights a number of dimensions of market efficiency and how they vary across markets. Competing with the largest, most sophisticated institutions that employ teams of highly trained analysts can make the prospect of active investing in large cap daunting. On the other hand, small-cap and international markets all score lower on these efficiency metrics and so present less of a challenge from the perspective of competition.

Data support the notion that active management can be more useful in less efficient markets. Figure 4 breaks down the percentage of active equity managers outperforming their benchmark over a rolling 12-month window by asset class. U.S. large cap, as we would expect, is the most difficult for active management to outperform the benchmark, with less than 50% of managers beating the Russell 1000 on average over rolling 12-month periods, net of fees. However, more than 50% of actively managed strategies in U.S. small cap, international developed, and emerging markets have outperformed the respective benchmarks, on average. As a result, our portfolio construction process leans more toward active management in those equity asset classes, while utilizing a greater mix of factor-based and passive vehicles within U.S. large cap.

While this discussion has thus far focused on equity markets, other asset classes offer unique opportunities and challenges for investors. Fixed income indices, for example, tend to be difficult to replicate in an ETF or index fund due to the large number of individual securities—such as the Barclays U.S. Corporate High Yield Index, which has almost 2,200 names. While a single corporation may only have one or two classes of common stock, it typically will have a relatively large set of different fixed income securities outstanding. These bonds are often of varied structures, maturities, and even credit levels.

Furthermore, the balance between primary markets (where securities are issued for the first time) and secondary markets (where existing securities are traded among investors) is much different in fixed income markets than it is in equity markets. The fixed income markets are more driven by the primary market, and individual bonds may not be available for purchase in the secondary market. These characteristics of fixed income markets present a challenge to passive strategies seeking to track a benchmark and, importantly, a potential opportunity to the active manager who can take advantage of pockets of illiquidity.

While fixed income generally has lower volatility compared to riskier asset classes, such as equities, these market characteristics can still offer active strategies the chance to generate alpha. It is also important to keep in mind that markets are dynamic and can become more or less efficient over time.

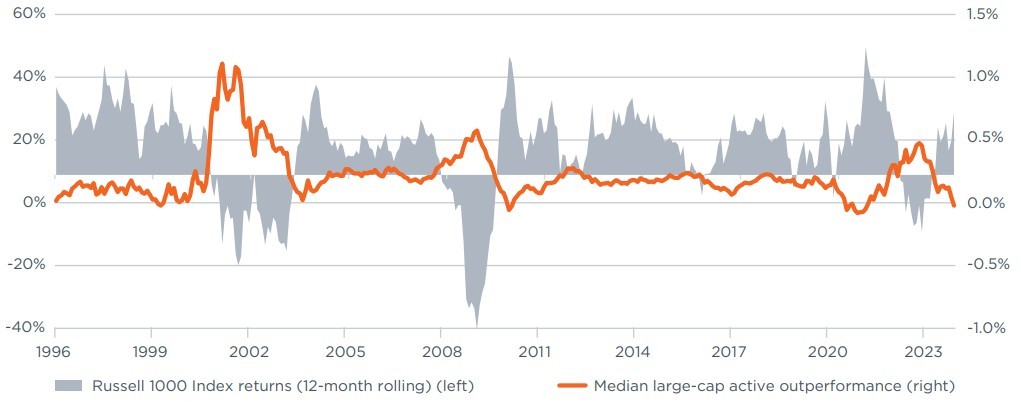

While market dislocations do occur and can offer unique opportunities, they happen relatively infrequently. Across market environments, our research has found that the performance advantage of active and passive large-cap strategies can vary based on market direction, volatility, and dispersion (the variance of returns for a group of stocks versus one another). This is one reason why we believe it is critical to assess a manager’s track record over a full market cycle. Although shifts in the market can be difficult to predict and therefore do not typically lend themselves to tactically adjusting the mix of active vs. passive, they can help explain when we would expect active or passive strategies to perform better. Active managers, for instance, have historically outperformed during market downturns. They have the flexibility to modify positioning in a way that passive managers cannot, which can contribute to greater outperformance, on average (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Active managers generally protect to the downside

The potential value of active management in bear markets

Data as of 12/31/2023.

Sources: eVestment, Bloomberg, Morningstar. Figure 5 presents Russell 1000 index returns versus returns (over Russell 1000) of the median US Large Cap Core active strategy (net of fees) using the eVestment universe. Both series are on a 12-month rolling basis. Net of fees performance is calculated by deducting the strategy’s highest applicable annual fee (0.95%) and separately managed account fee. Trust clients will also be charged fees for trust services that are in addition to fees for advisory and custody services, and such fees are not reflected in the performance presented. This chart and the following one draw on Parikh, McQuiston, and Zhi's “The Impact of Market Conditions on Active Equity Management,” The Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol. 44, No. 3 (2018), pp. 89–100.

We do filter the eVestment universe because there are some passive strategies and some low volatility/low beta strategies. We do our best to remove those because we want active (not passive) strategies and because low vol is more of a smart beta strategy. Excluding low vol also is a conservative approach in the sense that low vol/low beta strategies would exhibit an outperformance in down markets.

Investing involves risks, and you may incur a profit or a loss. Past performance cannot guarantee future results.

Indices are not available for direct investment. Investment in a security or strategy designed to replicate the performance of an index will incur expenses such as management fees and transaction costs which will reduce returns.

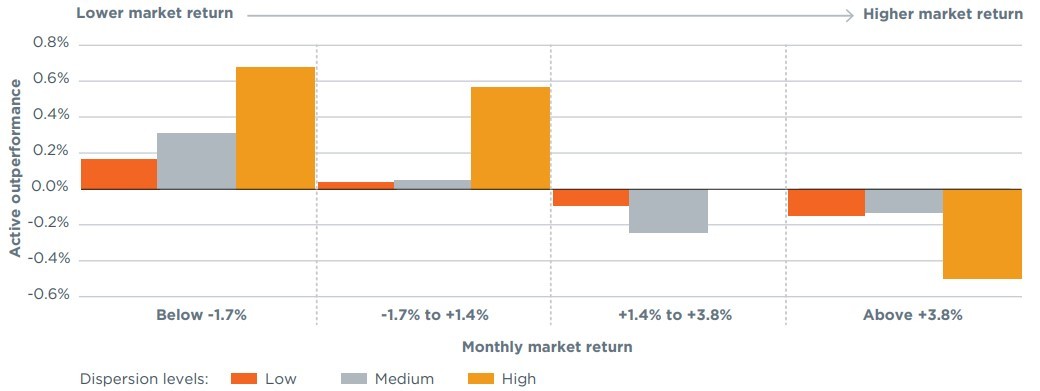

Second, active management tends to perform better when stocks are not moving in sync. During periods of low dispersion, stocks move in tandem. When dispersion is high, managers may have greater opportunity to enter or exit positions at favorable prices, offering more of a gateway for the skillful manager to add value. Of course, this can also lead to greater underperformance from less skilled active managers. We would expect, on average, periods of higher dispersion to be good for active managers. Indeed, this is illustrated in Figure 6. The groups of bars represent four quartiles (or levels) of market returns. As we have seen, a lower return is correlated with better active manager performance. Similarly, high dispersion benefits active managers in most of the quartiles of market return.

Figure 6: When active managers typically outperform

Active outperformance vs. market return and level of market dispersion

Data from 9/30/2001 through 12/31/2023.

Sources: eVestment, MSCI Barra, Bloomberg, Morningstar.

Figure 6 shows the median U.S. Large Cap Core active strategy out/underperformance (net of fees) versus the Russell 1000 using the eVestment universe. Active outperformance is segmented by quartile of market return and levels of market dispersion. Clusters of bars correspond to ranges of market return and the individual bars within clusters correspond to levels of market dispersion. The Russell 1000 index is used for market return and buckets are calculated on the entire time series. Market dispersion is defined as the cross-sectional standard deviation of iShares Russell 1000 ETF (IWB) holdings and it is bucketed into low (0-25th percentile), medium (25th-75th percentile) and high (75th to 100th percentile) segments, based on an expanding window. Returns are monthly.

We do filter the eVestment universe because there are some passive strategies and some low volatility/low beta strategies. We do our best to remove those because we want active (not passive) strategies and because low vol is more of a smart beta strategy. Excluding low vol also is a conservative approach in the sense that low vol/low beta strategies would exhibit an outperformance in down markets.

Investing involves risks, and you may incur a profit or a loss. Past performance cannot guarantee future results.

Indices are not available for direct investment. Investment in a security or strategy designed to replicate the performance of an index will incur expenses such as management fees and transaction costs which will reduce returns.

However, in the quartile with the strongest market returns, high dispersion is consistent with lower active performance. Why is this? One challenging scenario for active management is a bull market where index returns are driven by a handful of stocks. As an example, consider the first half of 2023: The S&P 500 was up almost 17% through June 30, 2023. However, this strong performance was due almost entirely to the “Magnificent 7” stocks (Apple, Microsoft, Google parent, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta Platforms, and Tesla), which were up over 86%. The average stock in the index, meanwhile, was up a more modest 5.6%.6

We would characterize the first half of 2023 as a low breadth or narrow market, meaning that a large number of firms did not participate in market returns. We’d also characterize the period as one of high concentration, in that index weights were clustered in a small number of names. In low breadth and high concentration environments like this one, dispersion is high, due to the massive outlier returns of a small group of stocks. This set of characteristics limits the opportunity for stock picking and thus active outperformance. Furthermore, active strategies often have an explicit cap on the weight their portfolio can have in each name (typically used as a means of managing risk), making it challenging to outperform when market breadth is low and market concentration is high.7 In 2023, we saw active large-cap strategies struggle in the first six months of the year. However, during the third quarter, the equity market corrected lower and actively managed strategies in our portfolios proved their worth. This performance continued into the end of the year and meant that portfolios—in no small part because of allocations to active strategies—outperformed their benchmarks over what was a very difficult year.

At Wilmington Trust, we believe that an optimal approach combines both passive and active strategies. Active management brings a unique contribution to portfolios, but allocating capital to active brings additional risk and expenses, necessitating expertise and thoughtful consideration on the part of investors. In-depth manager research and ongoing due diligence are critical to selecting the managers likely to perform best on a risk-adjusted basis going forward. The dynamics across asset classes and market environments can help identify when and where active management is most likely to add value to a portfolio. We aim to understand when a manager may outperform its benchmark and/or peers and when it may underperform, evaluating how well a manager has executed its strategy relative to expectations.

Our portfolio construction process incorporates both active and passive strategies, seeking to capitalize on the benefits of each approach and, for taxable investors, keeping tax efficiency top of mind. Our manager research team and due diligence process maintain a strong platform of active, passive, and smart beta strategies. Our beta, or market exposure, comes from active, smart beta, and passive strategies. Factor exposure is obtained via a combination of smart beta and active managers. When allocating to active managers, the hope is that they can provide alpha in portfolios beyond their market and factor exposures to justify their cost. For clients with sufficient assets to meet required strategy minimums, we often prioritize SMAs. Since SMAs hold individual names directly, they can be more tax efficient. SMAs also generally carry a lower fee than mutual fund equivalents.

Overall, we believe active management should play a larger role in less efficient asset classes, such as U.S. small cap, international equities, and fixed income, and be employed more selectively in more efficient asset classes, such as U.S. large cap. While we do not programmatically adjust the mix of active and passive based on expected changes in market volatility, breadth, and dispersion, we do use these factors to explain performance and may make strategic adjustments over time. The reality that it is difficult to predict market conditions cannot be emphasized enough.

However, in some scenarios, it can be sensible to adjust portfolios according to expectations for the future market environment. For instance, a strong equity market relative to history may be followed by elevated volatility, so a further tilt toward active management may be beneficial. This approach to manager selection added value in 2023 despite narrow market leadership, creating a difficult environment for U.S. large-cap active strategies. We will continue to elevate and evolve our investment process as industry and market conditions warrant.

1 Inigo Fraser Jenkins, et al., “The (Renewed) Case for Active Investing,” AllianceBernstein.com, November 7, 2022.

2 Cormac Mullen, “U.S. Stock Correlations Fall to Levels Seen Before Past Selloffs,” Bloomberg.com, January 25, 2021.

3 “Trends in the Expenses and Fees of Funds, 2022,” Investment Company Institute Research Perspective, Vol. 29, No. 3, March 2023.

4 http://www.morningstar.com/articles/390749/a-brief-history-of-indexing

5 Ryan Jackson, “Here’s Why Active ETFs Are So Hot Right Now,” morningstar.com, November 13, 2023.

6 Bloomberg Magnificent 7 Index, S&P 500 Equal Weight Index.

7 See, for instance, https://www.sec.gov/files/staff-report-threshold-limits-diversified-funds.pdf

DEFINITIONS

The Bloomberg U.S. Corporate High Yield Index, formerly Lehman Brothers U.S. High Yield Corporate Index, measures the performance of taxable, fixed-rate bonds issued by industrial, utility, and financial companies and rated below investment grade. Each issue in the index has at least one year left until maturity and an outstanding par value of at least $150 million.

MSCI EAFE Index is an equity index which captures large and mid-cap representation across 21 developed markets countries around the world, excluding the U.S. and Canada. With 902 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in each country.

MSCI Emerging Markets Index captures large- and mid-cap representation across 26 emerging markets countries. The index covers approximately 85% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization in each country.

Russell 1000® Index measures the performance of the 1,000 largest companies in the Russell 3000 Index, representing approximately 92% of the total market capitalization of the Russell 3000 Index.

Russell 2000 Index measures the performance of the 2,000 smallest companies in the Russell 3000 Index, which representsapproximately 8% of the total market capitalization of the Russell 3000 Index.

Russell 3000 Index measures the performance of the largest 3,000 U.S. companies representing approximately 96% of the investable U.S. equity market.

S&P 500 index measures the stock performance of 500 large companies listed on stock exchanges in the U.S. and is one of the most commonly followed equity indices.

DISCLOSURES

This article is for educational purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the sale of any financial product or service or as a determination that any investment strategy is suitable for a specific investor. Investors should seek financial advice regarding the suitability of any investment strategy based on their objectives, financial situations, and particular needs. This article is not designed or intended to provide financial, tax, legal, accounting, or other professional advice since such advice always requires consideration of individual circumstances. If professional advice is needed, the services of a professional advisor should be sought.

References to company names in this article are merely for explaining the market view and should not be construed as investment advice or investment recommendations of those companies.

References to specific securities are not intended and should not be relied upon as the basis for anyone to buy, sell, or hold any security. Holdings and sector allocations may not be representative of the portfolio manager’s current or future investments and are subject to change at any time.

The information in this article has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness are not guaranteed. The opinions, estimates, and projections constitute the judgment of Wilmington Trust and are subject to change without notice. The investments or investment strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for every investor. There is no assurance that any investment strategy will be successful.

Third-party trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners. Third parties referenced herein are independent companies and are not affiliated with M&T Bank or Wilmington Trust. Listing them does not suggest a recommendation or endorsement by Wilmington Trust.

Investing involves risks, and you may incur a profit or a loss. Past performance cannot guarantee future results.

Diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against a loss. There is no assurance that any investment strategy will succeed.

Stock risks:

Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this document will be profitable or equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s).

Securities markets are volatile and the market prices of securities may decline. Securities fluctuate in price based on changes in a company’s financial condition and overall market and economic conditions.

CFA® Institute marks are trademarks owned by the Chartered Financial Analyst® Institute.

Stay Informed

Subscribe

Ideas, analysis, and perspectives to help you make your next move with confidence.

What can we help you with today