Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

Equal Housing Lender. © 2026 M&T Bank. NMLS #381076. Member FDIC. All rights reserved.

The drama in Washington has taken center stage for investors who are grappling with the all-too-familiar game of chicken between the political parties on whether to raise the nation’s debt ceiling—the self-imposed borrowing limit that will impair the government’s ability to pay its bills or fund regular operations if the ceiling is reached. The date of hitting the ceiling (currently being referred to as the “X-date”) is uncertain as the Treasury can’t perfectly predict daily inflows and outflows, but Secretary Yellen has warned that date could be reached as early as June 1, and, if later, is likely within a few weeks of that date.

We are conscious of the rising risk of government default and, even without a default, the damage that could be done to investor portfolios. The near default in August 2011 provides the closest parallel. As we describe below, that experience dealt a blow to domestic equities that took more than six months to recover. Some of the damage comes from the intensity of near disaster, but also from the fiscal austerity that ensued. While we’re encouraged by optimism in recent days from House Majority Leader McCarthy and President Biden on the prospects for a deal, negotiating time is running out. We are advising clients to stay invested as the debt ceiling X-date approaches but are defensively positioned in portfolios in anticipation of a mild recession in 2023.

The ghost of debt ceilings past

The current standoff in Washington is eerily reminiscent of the Treasury’s close call with default in 2011. At that time, the X-date was August 2, 2011. Agreement was made on July 31 to raise the debt ceiling by $900 billion in exchange for spending cuts of roughly the same amount over 10 years. Despite the deal, Standard & Poor’s reduced its assessment of U.S. credit from “outstanding” (AAA) to “excellent” (AA+), the first such downgrade in the country’s history.

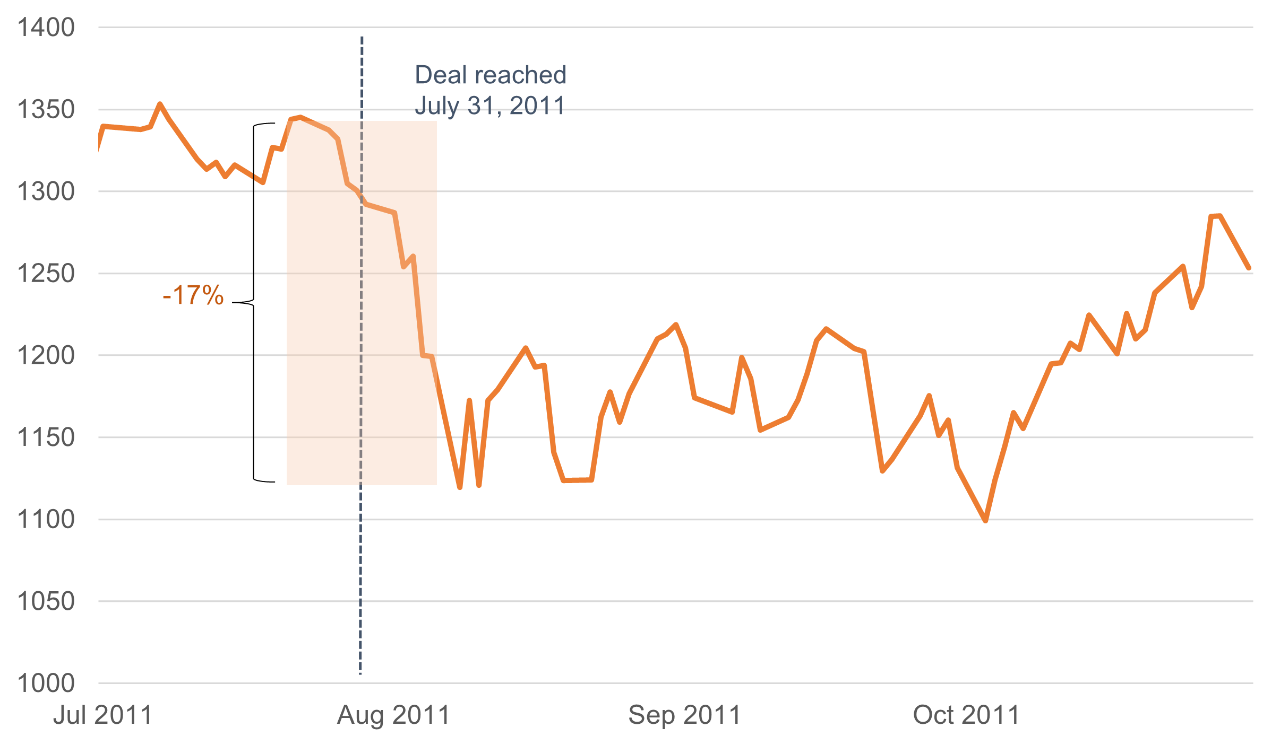

The reaction in financial markets was as vicious as it was swift, with U.S. large-cap equities, as measured by the S&P 500, falling 4% in the week leading up to the deal and then another 13% in the week following the downgrade (Figure 1). The market then meandered sideways in a +/-1% range for several months until finally breaking to the upside late that year. The equity market’s recovery was slow, taking seven months to recover the July 2011 peak. Domestic small-cap equities (not shown, measured by Russell 2000) were hit even harder with an instant bear market (-23%) over those initial two weeks and took eight months to recover the previous peak.

Importantly, the swoon in markets should not be completely attributed to the prospect for default, as much of the decline came after a deal was reached. Some of the pullback was in reaction to the first-ever downgrade of the nation’s creditworthiness, and still more can be attributed to investors pricing in the resulting fiscal austerity. Spending restraint coming from the deal resulted in federal spending detracting from overall growth for the ensuing four years. While the private economy grew about 2.5% per year over that time, the drag from federal spending brought overall growth down to roughly 2%.

Figure 1: S&P 500 index fell 17% over two weeks during the August 2011 episode

Source: Bloomberg. Data is June 30, 2011-October 31, 2011.

Past performance cannot guarantee future results. Indices are not available for direct investment. Investment in a security or strategy designed to replicate the performance of an index will incur expenses such as management fees and transaction costs which will reduce returns.

Déjà vu all over again

The current environment has uncanny parallels to the 2011 experience: a sitting Democrat president has a slight majority in the Senate but not the House, and the administration wants a “clean” lift of the debt ceiling with budget negotiations to follow, while the Republican-led House is insisting on spending cuts as part of the deal. The situation is changing by the day, and we are currently encouraged by positive statements from both sides that a deal can be reached without a default. It is likely that any deal will weigh on near-term economic growth but private market forecasters appear to have factored in weaker fiscal spending already.

The Republican-led House passed the “Limit, Save, Grow Act” on April 26 after much wrangling of the party’s membership. The bill would take an axe to federal spending by reducing discretionary outlays in Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 to FY 2022 levels and then limit annual increases thereafter to just 1%. It would also rescind COVID relief funds previously appropriated but not yet spent, repeal most energy and climate tax credit provisions from the climate-focused Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and prevent President Biden from enacting his student debt cancelation plan.

The hit to growth

The impact of the House bill in FY 2024 would be a 9.2% decline in discretionary spending relative to current baseline projections, a cut of $229 billion. Adjusting for inflation, we estimate that to be a -13% cut that year. Using Congressional Budget Office baseline figures and adjusting for inflation, we estimate a -1.1% hit to GDP growth, relative to the baseline. That is for FY 2024, which starts in the last calendar quarter of this year, just as we expect the U.S. economy would be in the midst of a mild recession. Therefore, as written, the House legislation could deepen a recession or frustrate a recovery.

Crucially, we do not expect the House bill to become law; it has no chance, especially heading into an election year. The bill serves as the starting point for House Republicans, and any eventual deal is likely to include milder cuts to spending and/or could spread the impact out over several years. The -1.1% hit to GDP described above should be seen as a worst-case scenario. Additionally, we see markets as likely already factoring in a cut to federal spending to some degree. The median economist GDP forecast for calendar year 2024 is 0.8%, a full percent below the CBO baseline, with a deceleration in government spending already baked in. Importantly, we are not taking a political stance on the matter, only calculating the near-term impacts on GDP. In the longer run, should nothing be done about the current spending projections, the economy would be impaired by unsustainable debt growth.

Figure 2: Economic projections by Fiscal Year and impact of House bill

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, WTIA.

Weighing portfolio risks

Investing around geopolitical events, including the debt ceiling, poses a unique set of challenges. A U.S. default falls into the category of a low-probability high-impact event. Even with the negotiating window closing and the Treasury’s X-date approaching, we place low odds on a default—in the range of 10%–15%. However, should a default occur, there would likely be few places to hide outside of cash or gold. We don’t believe a default or downgrade of the country’s debt rating is even partially priced into markets. Despite debt ceiling angst and multiple bank failures, the S&P 500 is now up almost 8% year to date, and investment-grade bonds have returned 2.8% as all but the shortest-term rates have moved lower since the start of the year. (1-, 3-, and 6-month Treasury bill yields are materially higher, reflecting increased risk of a near-term default.)

That said, we believe the best course of action is to remain invested. Odds remain overwhelmingly in the favor of a short-term extension or resolution, in which case any potential volatility between now and then will look like a blip on the radar for a long-term investor. Selling out of the market would generate taxes for many investors, while also adding the dilemma of when to reenter the market. It can, for a number of reasons, be difficult to muster the conviction to deploy previously invested cash back into the market. If a deal is struck as we expect, the market could experience a relief rally in the subsequent days or weeks. We would expect any relief rally to be modest, given the fact that markets have remained resilient in the lead-up to the X-date, but it could still present a situation where an investor is forced to buy back in at higher levels. This can make it tempting to remain in cash indefinitely, particularly if we get more signs of slowing economic growth through the summer.

The current environment may present some interesting opportunities for investors deploying new cash. Typically, when an investor has new money to invest—perhaps from the sale of a business or an inheritance—we advise investing that cash at regular intervals over a roughly 90-day window. (Your advisor can help think through individual circumstances that may necessitate a different plan.) Today, our advice is broadly consistent, but we think it makes sense to be a bit more flexible with deploying new cash. In some cases, it may be appropriate to elongate the investment window from 90 days to no more than 120 days. Or, in anticipation of potential volatility around the X-date and through the summer, investors could put money to work in smaller, more frequent chunks. For example, instead of investing a certain amount every month, investing a smaller amount every two weeks could achieve the same goals while taking advantage of an uptick in volatility. Despite near-term uncertainty, a methodical, timely investment strategy still gives long-term investors the best opportunity to compound returns over a multiyear timeframe.

In the tail-risk scenario of a default, we would expect correlations across equity asset classes and sectors to move closer to 1, with large but potentially short-term losses likely. (The duration of a pullback would be a function of how long after the X-date it takes to reach a resolution, and even in the worst case scenario, we would expect a resolution very shortly after a default.) In our base case where default is avoided, we think the focus of equity investors will quickly shift to the impact of reduced fiscal spending on economic growth. The estimates provided above illustrate the magnitude of the potential short-term hit to the economy, and by extension stocks, which could result from a debt ceiling deal. Headwinds would likely prove greater to more cyclical parts of the equity market. Small-cap equities, which typically exhibit a greater sensitivity to domestic growth, would be expected to underperform larger multinationals. In terms of factors, reduced economic growth and higher recession risks could extend enthusiasm for high-quality stocks exhibiting high profitability and low leverage. We are currently positioned with an underweight to U.S. small-cap equities versus our strategic benchmark and have shifted toward a larger allocation to high-quality equity strategies since the start of the year.

Core narrative

The risks around the debt ceiling are uncomfortably high—around 10%–15% risk of a default—while the shrinking timeline to strike a deal is increasing the urgency in Washington. Even in our base case of a resolution, the devil will be in the fiscal spending details, and a deal that favors the current Republican position could weigh more heavily on short-term prospects for the economy and cyclical equities.

Within a fully invested portfolio, we are already taking a more defensive posture with an above-benchmark weight to cash and investment-grade fixed income. We are underweight equities versus our strategic benchmark across U.S. small cap and international developed. This defensive positioning is due in part to debt ceiling risks but can mostly be attributed to our expectation for a U.S. recession in the second half of 2023—even without dramatic spending cuts from Congress. We expect an economic contraction to be short and shallow, but it could be worsened by higher levels of spending cuts. If our recession forecast comes to fruition, we expect U.S. large-cap equities to move lower, which could provide an opportunity to move back to a neutral or even overweight allocation to equities as we position for the next multiyear bull market.

Definitions

Russell 2000 Index measures the performance of approximately 2,000 smallest-cap American companies in the Russell 3000 Index, which is made up of 3,000 of the largest U.S. stocks.

S&P 500 index measures the performance of approximately 500 widely held common stocks listed on U.S. exchanges. Most of the stocks in the index are large-capitalization U.S. issues. The index accounts for roughly 75% of the total market capitalization of all U.S. equities.

Facts and views presented in this report have not been reviewed by, and may not reflect information known to, professionals in other business areas of Wilmington Trust or M&T Bank who may provide or seek to provide financial services to entities referred to in this report. M&T Bank and Wilmington Trust have established information barriers between their various business groups. As a result, M&T Bank and Wilmington Trust do not disclose certain client relationships with, or compensation received from, such entities in their reports.

The information on Wilmington Wire has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy and completeness are not guaranteed. The opinions, estimates, and projections constitute the judgment of Wilmington Trust and are subject to change without notice. This commentary is for informational purposes only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the sale of any financial product or service or a recommendation or determination that any investment strategy is suitable for a specific investor. Investors should seek financial advice regarding the suitability of any investment strategy based on the investor’s objectives, financial situation, and particular needs. Diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against a loss. There is no assurance that any investment strategy will succeed.

Past performance cannot guarantee future results. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or a loss.

Indexes are not available for direct investment. Investment in a security or strategy designed to replicate the performance of an index will incur expenses such as management fees and transaction costs which will reduce returns.

Reference to the company names mentioned in this blog is merely for explaining the market view and should not be construed as investment advice or investment recommendations of those companies. Third party trademarks and brands are the property of their respective owners.

The gold industry can be significantly affected by international monetary and political developments as well as supply and demand for gold and operational costs associated with mining.

Stay Informed

Subscribe

Ideas, analysis, and perspectives to help you make your next move with confidence.

What can we help you with today